Van het ene naar het andere / From one thing to another (English translation below)

Iedere dinsdag staan de vuilniszakken buiten te wachten, zwart en dichtgeknoopt. Een man op een fiets komt langs, maakt ze open en kijkt de inhoud zorgvuldig na. Hij neemt een beschadigd geëmailleerd bordje mee. De volgende man gaat grover te werk. Hij steekt met een mes de zakken kapot waarna de inhoud op straat rolt. Niets neemt hij mee. Ik hoop dat Sara Bjarland langs komt en een foto maakt van de halve gegrilde kip die eruit is gevallen. De deels opgegeten kip gun ik de zachte blik van haar camera. Ik haal de plant van de buren weer naar binnen. Wie weet kan wat magische liefde en iedere dag een beetje water de plant weer tot leven bewegen.

Sara Bjarland speurt tussen het vuilnis en neemt de kapotte, verlepte en besmeurde spullen onder haar hoede, mee naar haar atelier. Ze is de mantelmadonna voor al wat is afgedankt. Haar ogen raken het aan en haar blik brengt er, via de camera, leven in. Ze zet onverschilligheid om in een helende foto en geeft opnieuw waarde aan wat stuk en verbannen is.

‘Fotografie maakt van de hele wereld een begraafplaats. Fotografen zijn de connaisseursvan de schoonheid maar ze zijn ook, bewust of niet bewust de engelen die de dood vastleggen.’ schreef Susan Sontag, de grand old lady van de fotografie.Alles wordt stilgelegd, bevroren, voor de eeuwigheid, of née, tot de tijd het papier laat vergelen, de kleur uit de foto laat wegtrekken, de digitale bestanden onbruikbaar maakt.De vrouw die zo scherp kon zien dat de dood overal loerde, vanaf je geboorte met je meereist en je simpelweg opwacht, deed alles, maar dan ook alles, om in leven te blijven.Katie Roiphe schreef een verbijsterend verslag over de laatste jaren van Sontag; hoe ze tegen beter weten in iedere behandeling aangreep. Een beenmergtransplantatie vernietigde alle weerstand en haar lijf ontwikkelde overal zweren zodat zelfs slikken pijn deed. Het is niet te bevatten dat een vrouw van 71, tegen doktersadvies in, hier toch voor kiest. Geliefden zagen het met lede ogen aan maar ertegen in gaan was geen optie.‘Doorgaan met leven, misschien was dat wel haar manier om dood te gaan.’ De buitengewoon intelligente Sontag had de uitzonderlijkheid tot haar mythe gemaakt en het leek alsof ze ergens was gaan geloven dat ze aan de dood kon ontsnappen.Misschien is dat wel wat onze verhouding met de dood zo verstoort; wij mensen zijn onszelf te uitzonderlijk gaan vinden. We denken aan de dood te kunnen ontkomen,misschien niet met de verbeten overtuiging van Susan Sontag maar we geven niet snel op om het gevecht met de dood te winnen, ook al is de strijd bij voorbaat verloren, en weten we dit. Er kan immers niets misgaan: de dood is onvermijdelijk.Toch is de angst in ons gekropen.

Katie Roiphe wilde de dood niet begrijpen, maar‘zien’. Praten over de dood schrok haar af en ze dook in stapels boeken om zich een beeld te vormen.Ook Sara Bjarland wil de dood zien, en dat begon met de insecten in het zomerhuis.Ze groeide op in Finland en het zomerhuis was de spil van haar bestaan; een houten huis met veel ramen, de deuren naar het terras altijd open.

Een heel seizoen in de armen van de natuur, zowel binnen als buiten. Zomertijd is insectentijd, zeker in Finland, vol van muggen, knutjes, krekels, rietkevers, schorskevers en steekvliegen. Als kind probeert ze insecten in nood te redden. Heel voorzichtig werden ze in een glazen pot op een bedje van blaadjes gelegd en gevoerd. Honing, plantensap, haar eigen bloed desnoods.

Bjarland keek haar ogen uit: dat in drie stukjes opgedeelde lichaam, die transparante, ijle vleugels, de bijna onzichtbare ogen, en dan al die poten. Ze filmt de dood van een wesp, vol bewondering voor zijn gestreepte lijf, zijn pogingen overeind te komen om het uiteindelijk op te geven, een laatste beweging, en dan, rust. Née, wreed is het niet, eerder intiem. Het kijken naar het sterven van een wesp lijkt een homeopathisch middel om alvast te wennen aan de dood.

Volgens Sontag legt een foto vast wat gaat verdwijnen, maar de foto’s van Bjarland blikken vooruit.Haar wespenfilm en foto’s doen ons voorshands wennen aan het onafwendbare einde. Ze leidt ons een schemerwereld binnen waar onze noties over de dood langzaam verschuiven.

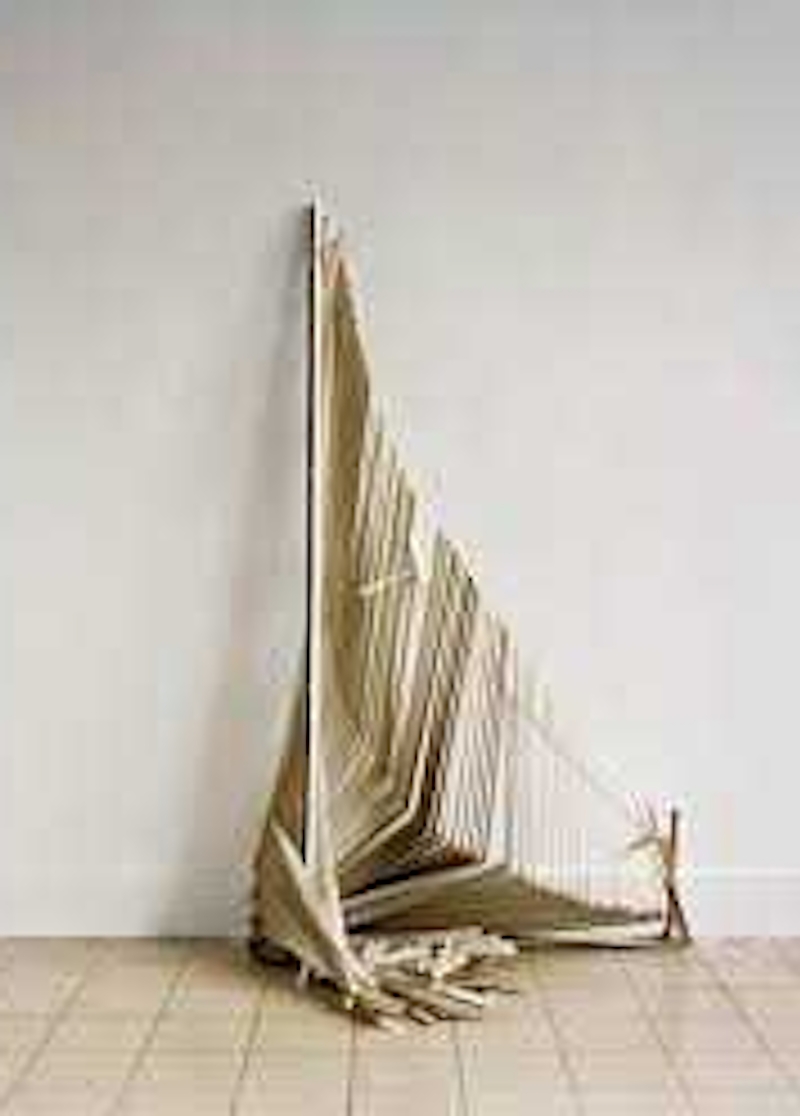

Bjarland ziet de dood overal om zich heen en tegelijk ook het leven dat daar weer doorheen schijnt. Een afgedankt sponsje, een dode muis, een apathisch hangende luxaflex. Ze verandert de verschijning van de dingen om ons heen, niet door er met haar handen aan te zitten, maar enkel door ernaar te kijken, via de camera. En dan zien wij het ook. De vergane paraplu ziet eruit als een vleermuis met een staart. Het gele blad van een verlepte vingerplant kijkt je verwijtend aan, vragend, smekend. De. bijna afgestorven berkenboom doet spinachtig aan.

Een eend die onderduikt is net een plastic zakje dat drijft. We zien tussenwezens met menselijke trekken. Een losse luxaflex die lui onderuit ligt.

En zo verandert ons inzicht. Misschien is de dood niet die rode streep door het leven. De overeenkomsten in vorm knagen aan de bestaande categorieën, van links rechts, zwart wit, man vrouw, mens dier. Van dood en leven. De strikte scheiding wordt opgeheven. Bjarland creëert een landschap waarin de grenzen vervagen, waarin een bijna dode plant een beroep op ons doet.‘Ik kijk veel naar kleine dode dingen’, schreef Bjarland, en op een of ander manier verbind ik deze met levende dingen. Levenloze dingen (zoals een gesmolten plastic krat), vind ik soms’dood’ lijken, en dit vind ik mooi want het suggereert dat ze misschien toch geleefd hebben. Een stuk plastic dat wappert in de wind is voor mij net zo levend als een vogel die vliegt. Ik probeer op een subtiele manier aandacht te geven aan dode, bijna dode, levenloze en levende dingen.’

‘Na het leven komt de dood, en dan is het afgelopen’ zegt de mens in al zijn grootspraak. Hoezo afgelopen? En vooral, waarom weten we dat zo zeker? In‘Het verborgen leven van bomen’ lees ik dat bomen met elkaar kunnen communiceren, dat ze zelfs kunnen voelen. Als de natuur een grote cyclus is, van seizoenen, een kringloop van mieren, rot hout en paddenstoelen, zijn wij mensen dan zo uitzonderlijk dat we erbuiten staan? Stof ben je, tot stof keer je terug.Het christelijk geloof heeft het idee van een begin en een einde geïntroduceerd waardoor het begrip lineaire tijd is ontstaan. Het verlichtingsdenken voegde daar het idee van vooruitgang aan toe.Maar de tijd zou ook een ritme kunnen zijn, dat zich blijft herhalen maar zoals de Canto Ostinato steeds net iets anders klinkt.

Of misschien cirkelt de tijd, zodat ze vooruit, maar ook achteruit kan gaan, zonder einde. Dan is er geen vijand die bestreden moet worden want de dood brengt je terug naar iets dat je al kent, ooit was je daar al. Ieder idee over tijd is een concept in onze geest.

Misschien bestaan we als mens niet alleen uit stof maar ook uit de ongrijpbare vorm van energie die chinezen qi noemen.

De Chinese filosoof Zhuang Zi was intens verdrietig na het overlijden van zijn vrouw, totdat hij ruimte gaf aan een ander idee over haar heengaan.‘In al die chaos en verwarring veranderde er iets en er was qi. En het qi veranderde en werd vorm. De vorm veranderde en zij werd levend. En nu is er weer iets veranderd en is ze dood. Het is als de kringloop van de vier seizoenen: lente, zomer, herfst en winter.’

Susan Sontag overleed op 28 december 2004. Middels haar boeken blijven we met haar in gesprek, zoals in deze tekst. En wie weet praat haar zoon nog met haar, of een van haar ex-geliefden.

Nick Cave leeft voor eeuwig met zijn zoon die op vijftienjarige leeftijd overleed.‘I feel the presence of my son, all around, but he may not be there. I hear him talk to me, parent me, guide me, though he may not be there. He visits Susie in her sleep regularly, speaks to her, comforts her, but he may not be there. Dread grief trails bright phantoms in its wake. These spirits are ideas, essentially. They are our stunned imaginations reawakening after the calamity. Like ideas, these spirits speak of possibility. Follow your ideas, because on the other side of the idea is change and growth and redemption. Create your spirits. Call to them. Will them alive. Speak to them. It is their impossible and ghostly hands that draw us back to the world from which we were jettisoned; better now and unimaginably changed.

’Misschien zweven de doden als geesten om ons heen, misschien zitten ze op een schouder en kijken mee, of is die witte vogel hun spreekbuis. Misschien zijn de pratende doden onze hersenschimmen. Met haar verschuivende en overlappende beelden suggereert Sara Bjarland iets over een tussengebied, ze puzzelt met de dood, ze oppert mogelijkheden. Het is een open veld waarin we mogen meekijken.

From one thing to another

Every Tuesday, the bin bags wait outside, black and tied at the top. A man on a bike comes by, opens them and checks the contents carefully. He takes a damaged small enamel plate away with him. The next man sets about it more crudely. He stabs the bags open with a knife, making the contents roll out onto the street. He doesn’t take anything. I hope that Sara Bjarland will come along and take a photo of the half of a grilled chicken that has fallen out. I think the partly eaten chicken deserves the soft glance of her camera. I take the neighbours’ plant indoors again. Who knows, some magical love and a little water every day may bring the plant back to life.

Sara Bjarland hunts through the rubbish and takes the broken, wilted and stained things into her care, to her studio. She is the mantle Madonna for all that is discarded. Her eyes touch it and her glance brings life into it, via the camera. She transforms indifference into a healing photo and gives renewed value to things that are broken and banished.

‘Photography converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers are the connoisseurs of beauty but they are also, wittingly or unwittingly, the recording-angels of death,’ wrote Susan Sontag, the grand old lady of photography. Everything is halted, frozen, for eternity, or no, until time turns the paper yellow, makes the colour fade from the photo, makes the digital files unusable.

The woman who saw so clearly that death lurks everywhere, travels with you from the time of your birth and simply waits for you, did everything, absolutely everything, to stay alive. Katie Roiphe wrote an astonishing report about Sontag’s last years; how she seized upon each treatment, against her better judgement. A bone marrow transplant destroyed her immune system and her body developed sores everywhere so that even swallowing was painful. It is incomprehensible that a woman of 71 would choose for this, going against doctors’ advice. Her loved ones looked on sorrowfully but opposing it was not an option.

‘Continuing with life, perhaps that was her way of dying.’ Exceptionally intelligent, Sontag had made exceptionality her myth and it seemed as if she had somehow begun to believe that she could escape death.

Perhaps this is what disturbs our relationship with death so much; we humans have come to regard ourselves as too exceptional. We think we can evade death, perhaps not with the dogged conviction of Susan Sontag, but we don’t give up easily in trying to win the battle with death, even if the struggle is lost in advance, and we know it. Nothing can go wrong, after all: death is inevitable. Yet fear has taken hold of us.

Katie Roiphe did not want to understand death, but to ‘see’ it. Speaking about death put her off and she dived into piles of books to form a picture for herself.

Sara Bjarland also wants to see death, and this began with the insects in the summerhouse. She grew up in Finland and the summerhouse was the hub of her existence; a wooden house with lots of windows, the doors to the terrace always open. In the arms of nature for an entire season, both inside and outdoors. Summertime is insect-time, certainly in Finland, full of mosquitoes, midges, crickets, [2] leaf beetles, bark beetles and horseflies. As a child, she tried to rescue insects in distress. They were laid in a glass jar very carefully on a little bed of leaves, and were fed. Honey, plant sap, her own blood if necessary.

Bjarland feasted her eyes: that body divided into three small parts, those transparent, ethereal wings, the almost invisible eyes, and then all those legs. She films the death of a wasp, full of admiration for its striped body, its attempts to stand up, only to finally give up, a last movement, and then, rest. No, it is not cruel, but rather, intimate. Watching the death of a wasp seems like a homeopathic remedy to already get used to death. In Sontag’s view, a photo captures something that is going to disappear, but Bjarland’s photos are forward-looking. Her wasp-film and photos allow us to get used to the inevitable end before it comes. She leads us into a twilight zone where our ideas about death slowly shift.

Bjarland sees death everywhere around her and at the same time also the life that shines through it again. A discarded sponge, a dead mouse, Venetian blinds hanging apathetically. She changes the appearance of the things around us, not by touching them with her hands, but just by looking at them, via the camera. And then we see it too. The dilapidated umbrella looks like a bat with a tail. The yellow leaf of a wilted paperplant looks at you reproachfully, asking, begging. The nearly dead birch tree looks spider-like. A duck diving under water is like a floating plastic bag. We see in-between beings with human traits. Loose Venetian blinds, lounging lazily.

And so our understanding changes. Perhaps death is not the red line running through life. The similarities in shape gnaw away at the existing categories, of left-right, black-white, man-woman, human-animal. Of death and life. The strict division is removed.

Bjarland creates a landscape in which the boundaries blur, in which an almost dead plant calls out to us. ‘I look at small dead things a lot,’ wrote Bjarland, ‘and then I somehow connect them with living things. I sometimes find that lifeless things (such as a melted plastic crate) seem ‘dead’, and I find this beautiful because it suggests that they may in fact have lived. A piece of plastic flapping in the wind is just as alive for me as a bird in flight. I try to focus in a subtle way on dead, nearly dead, lifeless and living things.’

(vertaling Kathryn Westerveld)

‘After life comes death, and then it’s over,’ says man arrogantly. How do you mean, over? And above all, why are we so sure about that? In ‘The Hidden Life of Trees’, I read that trees can communicate with each other, that they can even feel. If nature is one great cycle, of seasons, of ants, rotten wood and mushrooms, are we humans then so exceptional that we stand outside of this? Dust you are, to dust you will return.

The Christian faith introduced the idea of a beginning and an end, thereby giving rise to the concept of linear time. Enlightenment thinking added to this the idea of progress.

But time could also be a rhythm that keeps repeating itself yet, like the Canto Ostinato, always sounds just a bit different. Or perhaps time circles, so that it can go forwards but also backwards, without an end. Then there is no enemy who must be fought because death brings you back to something that you already know, you were already there at some point. Any idea about time is a concept in our mind.

Perhaps as humans we consist not only of dust but also of the intangible form of energy that the Chinese call qi. The Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zi was intensely sad after the death of his wife, until he became open to another idea about her passing. ‘In all that chaos and confusion, something changed and there was qi. And the qi

changed and took shape. The shape changed and she came to life. And now something else has changed and she is dead. It is like the cycle of the four seasons: spring, summer, autumn and winter.’

Susan Sontag died on 28 December 2004. Through her books we remain in contact with her, as in this text. And, who knows, perhaps her son still speaks with her, or one of her ex-lovers.

Nick Cave lives forever with his son who died at the age of fifteen. ‘I feel the presence of my son, all around, but he may not be there. I hear him talk to me, parent me, guide me, though he may not be there. He visits Susie in her sleep regularly, speaks to her, comforts her, but he may not be there. Dread grief trails bright phantoms in its wake. These spirits are ideas, essentially. They are our stunned imaginations reawakening after the calamity. Like ideas, these spirits speak of possibility. Follow your ideas, because on the other side of the idea is change and growth and redemption. Create your spirits. Call to them. Will them alive. Speak to them. It is their impossible and ghostly hands that draw us back to the world from which we were jettisoned; better now and unimaginably changed.’

Perhaps the dead are floating around us as spirits, perhaps they are sitting on a shoulder and watching with us, or perhaps that white bird is their mouthpiece. Perhaps the talking dead are shadows of our minds. With her shifting and overlapping images, Sara Bjarland suggests something about an in-between area, she puzzles with death, she puts forward possibilities. It is an open space that we may look into over her shoulder.

OR: sign (‘bordje’ = ‘small plate’ en ‘sign’

OR cricket bread?? (krekelbrood)